Following the success of Andrew Skelton’s ‘Walls have Ears’ series, he has created a bonus third part on lost and hidden walls that cannot be seen today but have been previously photographed and/or documented. With extra special thanks to Skelton for this series, we hope you have enjoyed it!

Bonus Part 3: Lost and Hidden Historic Walls in the London Borough of Sutton

At the end of the second part of my ‘Walls have Ears’ blog, I highlighted a shop-divider in Wallington, which has been inelegantly grafted onto a Victorian semi-detached house near the railway station. Looking slightly out-of-place, it is possible that it is a reused piece of ornamental brickwork from a demolished structure. It reminded me that there have been a number of walls in the borough that have either not survived, but were fortunately recorded before they disappeared or are hidden from view today by later construction. In this last Blog on Sutton’s walls, I will be looking at a few examples of these which have been recorded by in this way over the years.

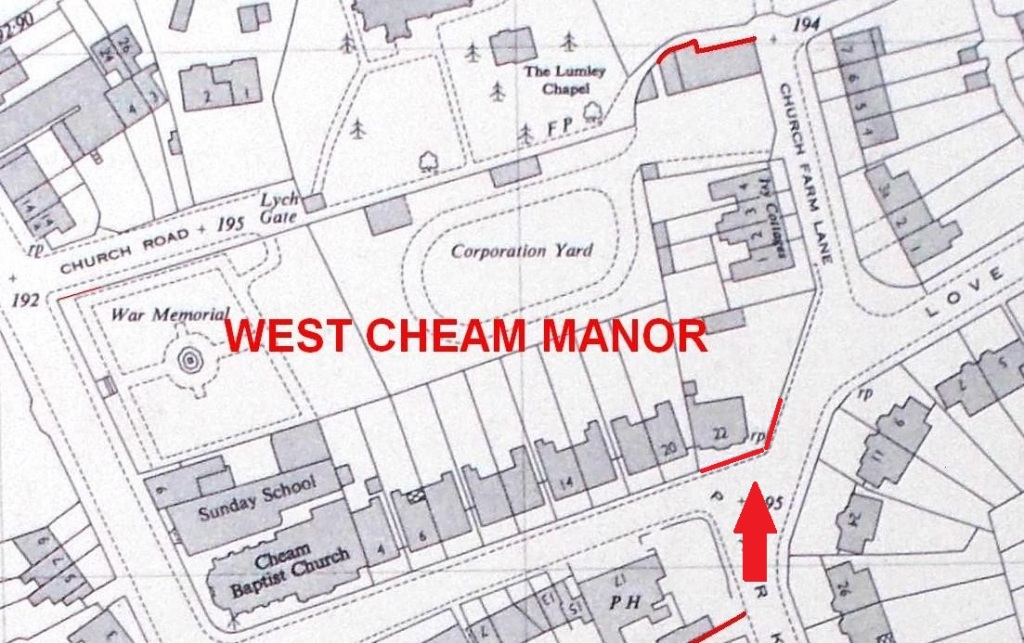

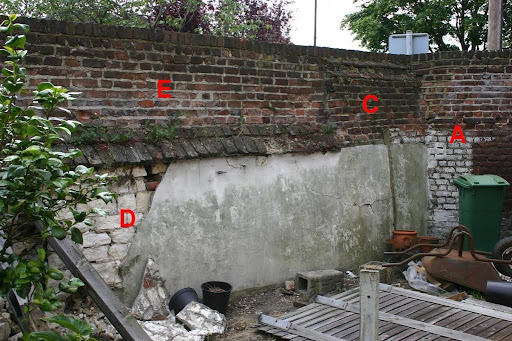

The first of these is in Cheam, on a site which I mentioned in the first Blog – the Factory Garden on the site of West Cheam Manor. On the corner of Park Lane and Church Farm Lane, John Phillips in 2004 photographed a stretch of the boundary wall deemed to be unsafe and due to be demolished. Fairly plain from the outside, the internal elevation shows a mixture of building phases. The western section (A) is of brick, and is imperfectly bonded into the longer eastern section (B), which comprises a shortened thickened section with a double offset (C), which terminates a chalk block section capped by a pyramidal coping (D), the chalk block does not appear as well worked as the surviving one behind the stables (blog 1). This was increased in height by nine courses of brickwork (E). Now, without documentary evidence, it is difficult to say if these phases took place over 1, 5, 10, 20 or more years; all that can be said with some certainty is that the earliest phase of this wall can be no earlier than about 1746, when the garden was extended in this area for the Duke of Bedford. Thanks to John, this important evidence for West Cheam Manor and its gardens survives – even if the structure does not!

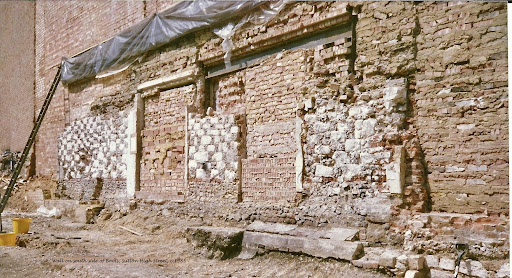

Moving into Sutton, there are two interesting ‘lost’ walls, of which one has survived but is completely invisible to view. The latter is almost certainly the earliest structure surviving in Sutton, dating at least from the 17th century, and employs an early construction technique found elsewhere in the borough. Once again chalk blocks are the main decorative material, but are used here in chequer work with knapped flint; the grey-black flint cores grouped in rough squares create a fine decorative contrast with the chalk block. This impressive wall is set on a levelling single course of brickwork laid over a flint foundation, and has been itself used as the base of a modern wall forming the south side of Boots the Chemist. It has been interpreted as a side wall for a house rather than a boundary wall although, of course, it has acted as such for many years. When the premises were rebuilt in the 1990s the wall was exposed, recorded and then hidden again but could be viewed through small decorative lozenge shaped openings in Clarke’s Shoe Shop. Today, even these are hidden from view behind panelling. Despite that, it is a precious survival despite not being visible to the public and it raises the hope that, along the High Street, similar examples await to be discovered. In his Survey of Early Buildings in Sutton, John Phillips records another chalk and flint boundary wall around the Old Rectory Garden, also demolished, and you can still see one near Nonsuch Mansion and inside Honeywood.

The other wall, demolished about a decade ago, was in the grounds of Sutton Court; a major pre-suburban house situated immediately west of the Old Chalk Pit where B&Q is today. Apparently rebuilt in the early 19th century and shorn of its grounds in the late 1870s, the house survived into the early 20th century. To its south was a series of walled gardens with an attached building situated at the southern end of a long stretch of chalk block, flint and brick wall close to the railway line. When Sutton Court Road was driven through the estate in the 1880s, this garden wall was used as a boundary between number 2 and a service road behind the a terrace of shops and maisonettes, built as a speculation for John Ruck of Sutton Court in the late 1860s on the site of his walled gardens. Ordnance Survey maps indicate that the garden building survived intact into the later 20th century. In the 1970s and 1980s the former Heritage Officer the late Doug Cluett pointed it out on his Local History Walks, and in 1986 Joy Reynard followed this up by venturing down the service road with her camera; all that remained to photograph was the outer wall with doors, windows and thin rectangular vents which point to it being the rear wall of a bothy and/or greenhouse. Although covered in vegetation, another photograph Joy took looking south down the service road clearly shows chalk fabric where the wall had been broken through. With the extensive redevelopment of that area in the mid 2010s, the wall was finally demolished, and nothing now of any antiquity survives in the south-east quarter of Sutton.

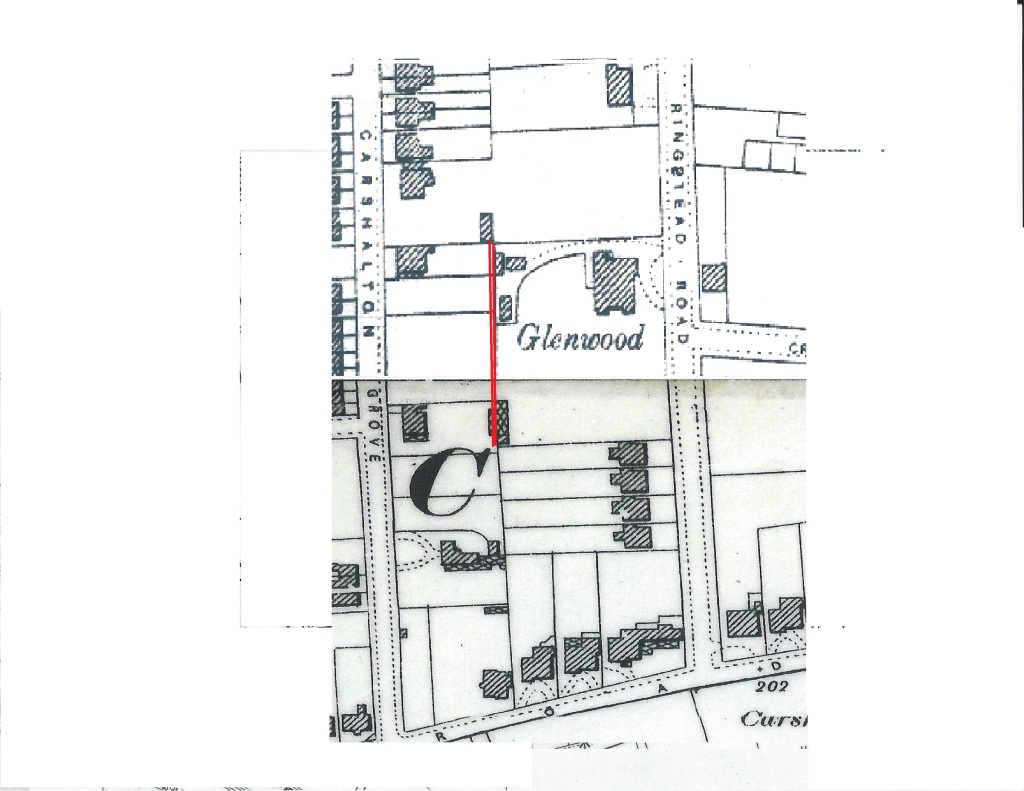

Our final example survives intact, but is barely visible to the public and only dates to the later 19th century. Large suburban houses surrounded by grounds of more than half an acre or more were built on former agricultural land during the Victorian period. These establishments were equipped with a full complement of facilities; yards, greenhouses with their heating apparatus, stables and summerhouses – all set within a pattern of tennis courts, parterres and orchards, all now gone. But boundary walls hidden at the end of later gardens can hint at past glories; one particular house – Glenwood – on the border of Sutton and Carshalton along Ringstead Road, had a wall along its western side which was designed as a specific part of the garden landscape. Now standing as a boundary between higher density suburban development this wall is highly ornamented with a serpentine profile and pilaster buttresses topped with terracotta ball-finials. It has a high shaped gable-style centre piece which formed the focus of an ‘arbour’, enclosed by tree-lines shielding the occupants from the tennis court and the house beyond. As with so many examples of this class of house, nothing else survives but this fine boundary wall and some of the smaller, less conspicuous property walls visible along Carshalton Grove.

It has been possible to work out the significance of these walls, existing or not, using maps and documents in the Archives and Local Studies collections. In the case of Glenwood, the 1910 Sale Particulars has a good description and beautifully illustrated plan clearly depicting the features I have described above; these have allowed the interpretation of the ornamented wall. You can see this document (ref 62/53/19) by booking an appointment with the Borough Archivist at the Local Studies Room – if you have an old wall near or on your property, why not do the same and visit the Archives to carry out a bit of research to find out its history?

Andrew Skelton – with thanks to John Phillips and Joy Reynard