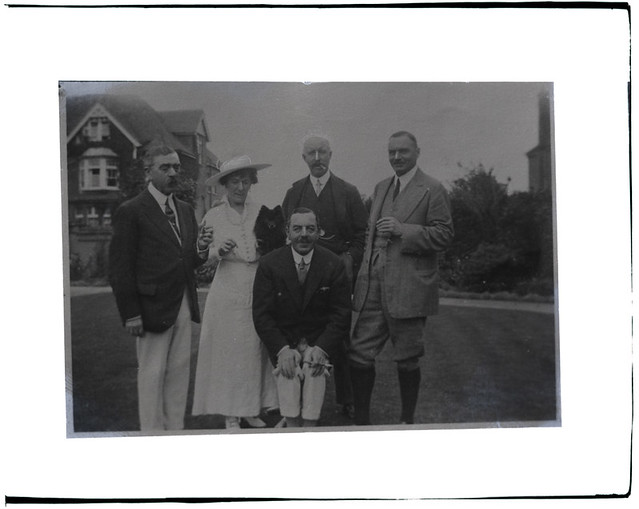

Thinking about a blog topic for today, I searched among our scanned plates for any images dated in the first week of September. The first of two images I found was this, of an Arnell Esq. The image is clearly a copy made of another photograph and even exhibits the name of the original photographer ‘Freeman’ clearly in embossed lettering on both the image and the mount.

A surprisingly large number of the plates in our collection appear to be copies of other images and this has led us to believe that it must have been a lucrative part of Knights-Whittome’s business to create additional copies of treasured family photographs for his clients. I have been unable to find anything written about this practice but it makes sense that this occurred in a time when photographers retained the glass negatives of all their images and provided clients only with a non-fixed proof image and the prints of their preferred images in whichever format they chose. This is not to say however that the practice was strictly legal. UK Copyright law today states that the period of copyright runs for 70 years from the end of the year in which the author/photographer dies. In the case of David Knights-Whittome for example, who died 4 November 1943, copyright only expired at the end of 2013, just a year prior to the start of this project.

Reading up on how copyright law differed 100 years ago has proven confusing and I must admit I am hazy as to the ins and outs of the historical laws in regard to this practice.

The AHRC website Primary Sources on Copyright offered me the clearest insight into the 1862 Copyright in Works of Fine Art Bill which set the agenda for the Edwardian period during which Knights-Whittome was working. For the first time, photography was included in the bill. The following text, taken verbatim from an article by R Deazley on this website (I could not explain it any better myself) explains why this was a controversial decision:

“….that photography was to be included within the remit of the legislation gave rise to considerable parliamentary debate. In the Commons, a Mr. Lewis raised the issue as to whether “it would be dangerous at present to include photographs” in an Act of this kind given that “[p]hotography was not a fine art, but a mechanical process”. Palmer responded that while “strictly and technically, a photograph was not in one sense to be treated as a work of fine art”, nevertheless, “very considerable expense was frequently incurred in obtaining good photographs”. He continued:

“Persons had gone to foreign countries – to the Crimea, Syria and Egypt – for the purpose of obtaining a valuable series of photographs, and had thus entailed upon themselves a large expenditure of time, labour and money. Was it just that the moment they returned home other persons should be allowed, by obtaining negatives from their positives, to enrich themselves at their expense?”

….Having posed his rhetorical question, Palmer continued that he would not consent to exclude photographs from the Bill…….

That was not the only objection to the inclusion of photography within the remit of the proposed legislation. When the Bill was read for the second time before the Lords, Earl Stanhope (previously Lord Mahon) (1805-1875), who had been instrumental in securing the passage of the Copyright Act 1842, voiced further misgivings. While he supported the current Bill upon the principle that “a man should be protected in the enjoyment of his intellectual productions” whether literary or artistic, nevertheless, Stanhope considered, it exhibited “one or two points of difficulty” especially in relation to photographs. In particular he observed that:

“It was quite possible for two or more persons to take photographs of the same scene, building, or work of art from the same spot, and under the same circumstances, and of course producing similar results; and to give a copyright in such cases [was] very likely to occasion dispute and litigation. A person, for instance, might make a photograph copy of a photograph – say of the Colisæum – originally taken by another; who could say that the copy was not the original photograph?”

Under such circumstances, he continued, he could not envisage how it was practicable “to enforce such a copyright”. Bethell, now the Lord Chancellor, sought to assuage Stanhope’s concerns commenting that “the copy of a photograph might be sufficiently detected, as it would hardly be possible for two persons to produce representations of the same object under exactly the same conditions of light, position and other circumstances”. As with the earlier objections of Lewis, the point was ultimately conceded. When the Bill received the Royal Assent, on 29 July 1862, paintings, drawings, and photographs all enjoyed equal status under the new legislation. Copyright was to last for the life of the author and seven years after his or her death…the copyright term was now to be calculated only by reference to the life and death of the author.”

Stationers Hall, 1831 Engraving. Image courtesy of Fotolibra.

Prior to 1862, the big difference had been that copyright was never assumed “…no copyright shall be acquired by the author of a work except upon condition of its being registered.” Registration, at Stationers Hall, London, was still possible but entirely optional. The new bill assumed copyright for all works of art created from this date and indeed, not only was it unnecessary to register the work, it was unnecessary for it to even be “legibly signed, painted, engraved, printed, stamped, or otherwise marked upon the Face or some conspicuous Part of such Work.” (Draft Bill, 15 April 1861, clause 5.) The Bill simply allowed for copyright protection from the point of the author’s creation of the work. It is here that my understanding of the legal complexities of copying photographs becomes hazy. The article goes on to describe how copyright may be forfeited by the creator of the work:

“..the 1862 Bill revised the original wording of the previous Bill to provide that when any work was sold for the first time, “the Person so selling or disposing of the same shall not retain the Copyright thereof unless it be expressly reserved to him by Agreement in Writing, signed at or before the Time of such Sale or Disposition, by the Vendee or Assignee of the Painting or Drawing”. This, in the opinion of the Athenæum, was scarcely an improvement, in that it still offered no benefit or security for the purchaser of the picture:

“As the section stands, it means that when an artist has acquired a copyright by executing a work, that copyright is to cease, unless when he first sells such work his purchaser signs an agreement for the purpose of reserving the copyright to the artist. It follows, that where an artist thus reserves his copyright, he will have the exclusive privilege of making as many copies or repetitions of his work as he pleases; – but where the purchaser declines to enter into such an agreement … then that copyright will thereupon cease, and the artist will consequently, as at present, be able to make and sell as many unauthorized copies and repetitions of the work as he please; the only difference being, that he will not have the monopoly for that purpose.”

As was the case with the provision on registration, the substance of the Bill was amended in the Lords, and when the Act was passed it included the presumption that, when first sold, the copyright in a work passed to the purchaser at the same time unless the seller specifically retained the copyright therein by “agreement in writing”. Moreover, the final version of the Act also extended this presumption of copyright ownership to those individuals who commissioned specific works for “a good or a valuable consideration”.

Going by this information, it seems that unless the photographer had expressly reserved his copyright, Knights-Whittome may well have been within the law to reproduce these images on the request of his clients. Without the evidence of this ‘permission’ however, we shall never know.

An original application for the registration of photographic copyright made by David Knights-Whittome. Now held in COPY1 at The National Archives.

We know that Knights-Whittome was well aware of copyright laws. He voluntarily registered his own early works at Stationers Hall with records now held in the COPY1 collection at The National Archives and his business activities demonstrate that he was commercially astute. It is unlikely he would have naively undertaken this kind of work without understanding the implications thereof. My instinct tells me that while images of public spaces, events and famous/royal personages were most probably strictly governed, the reproduction of family photographs on request of a paying private client was probably something that was widely done by high street studio photographers with a blind eye turned to the strict legalities. Many of the copies we have found so far are dated between 1906-1910, meaning that they fell within the remit of the 1862 Copyright Act detailed above. Knights-Whittome remained in business until 1917 however meaning that these laws were superseded in 1911, when a further act simplified and consolidated the law. This has subsequently happened a number of times, for example with the 1988 Act and most recently the Copyright and Rights in Performances (Research, Education, Libraries and Archives) Regulations 2014. While details and complexities have necessarily changed as the means of artistic creation and reproduction have multiplied, the basic principles of copyright remain the same with an improved balance between user and copyright owner.

Sadly, we do not, for the most part, have information about these copied images. They are recorded simply with the name of the client who commissioned the copy to be made. This is a pity as some of these images are very interesting and show Victorian costume, scenes taken ‘on location’ and offer an insight into an earlier style of photography. An album of these copies can be seen on the project Flickr site.

Sources: Deazley, R. (2008) ‘Commentary on Fine Arts Copyright Act 1862′, in Primary Sources on Copyright (1450-1900), eds L. Bently & M. Kretschmer, www.copyrighthistory.org