Our blog site looks at lots of areas of local history. However, it takes its name ‘The Past on Glass’ from a specific collection; that of the photographer, David Knights-Whittome and the glass plate portraits he took between 1905 and 1918. The digitised images are available on our Flickr site. This blog site was originally set up to document and uncover the people behind these photographs and has now progressed to encompass more stories of the local area through the years. Today, our long-time volunteer, Elizabeth, returns to the David Knights-Whittome collection to discuss those that lived and worked directly around Sutton Station. It is an exploration of Sutton during the 20th century, centred on these portraits that have illuminated many parts of our local history. Over to you Elizabeth, with many thanks.

David Knights-Whittome moved to Sutton High Street in 1904, taking over the photographic studio at No.18, run by Reginald Ellis. It was a good location for a young and dynamic photographer; the upper end of the High Street was a mix of old, established shops – a butcher, a baker, a bank, a draper – and newer shops, such as chain stores, or those providing new goods or services – electricians, plumbers, a gas showroom. Sutton was a busy and cosmopolitan town with a growing population in 1904 of over 17,000. The railway station, at the top of the rise, was a busy hub with fast trains running to London in 20 minutes, and many of the passengers passing through the High Street were probably photographed by Mr Knights-Whittome. But, he also photographed some of the shopkeepers, workers, inhabitants of the shops and houses surrounding the station, and the unique collection he left behind gives us a glimpse of those people who lived and worked in the High Street.

Railways, at the turn of the 20th century, were the main method of land transport. Trams did not arrive in Sutton until 1908, running from the bottom of the High Street along Westmead Road and Croydon. Another Sutton Archives volunteer, Clive, has already taken us on an historical journey of a local bus route, the first part of seven available here.

Sutton Station had opened in 1847 on the line between Epsom and Croydon, and was run by the London, Brighton and South Coast Company (LSBC). Further rail links were added, with a line to Epsom Downs, and a new route to London via Mitcham and Tulse Hill.

The railway offered good employment to local men and boys: all had to be recommended by a local person, such as the vicar, a school master, or the army. There were goods clerks, parcel clerks, booking clerks, telegraph clerks, ticket collectors, signal lads, porters, passenger guards, carmen, shunters, station inspectors, and, in charge overall, was the Station Master. This is Charles Gardner, Station Master from 1901 until 1913, photographed by Knights-Whittome in 1905.

He would have been an imposing figure, standing on the station forecourt welcoming passengers, or perhaps he was inside supervising the large number of people working under him – in the offices or on the tracks. The railway also offered a career – most of the young men that Charles supervised would eventually move to different stations on the line and work their way up to better paid roles. Charles himself had started work for LBSC in 1870, aged 18, as a booking clerk at Queen’s Road Station, earning 10s 6d a week. He moved to Sydenham at the end of that year, and then to Clapham Junction in 1873, earning £1 a week. He rapidly progressed, becoming Station Master at Old Kent Road in 1881, with a uniform supplied by LBSC and an annual salary of £110. His next move was to Purley in 1891, and eventually to Sutton in 1901, where he stayed until his retirement. Charles and his family – his wife, Harriet, and their children, Leslie and Bessie – all lived at Station House (now demolished) at the top of the High Street. Charles retired in 1912 on a salary of £180.

Signal lads, such as Albert Jordan from Cheam, who joined in 1904, aged 15, earned 7 shillings a week, rising to 14s in 1906. Albert’s father was also a railway signalman, and his brother, Charles, was a telegraph messenger. Albert stayed with LBSC for his working life – although moving around to different nearby stations. By 1915, he was earning £1 3s! Booking clerks, such as Ernest Pharoah, earned £1 15s a week in 1914. Ernest, photographed by Knights-Whittome in 1907 [picture on the left] was from Wallington and joined LSBC straight from school. Here he is photographed several years later with his wife, Eliza [picture on the right]. Ernest, too, stayed with LBSC, and, like many other families, his son George also joined LBSC as a railway clerk.

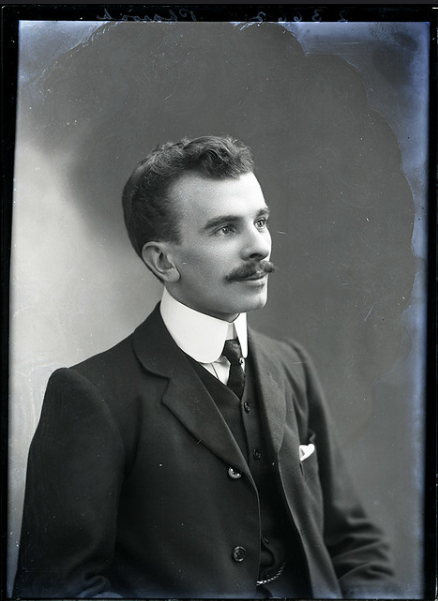

Looking back to Charles Gardner, although his father was a carpenter, Charles and his brothers saw the opportunities that could be gained from secure employment with railway companies such as LBSC. Charles’ son, Leslie, also joined LBSC – starting work as a clerk at Leatherhead station. There were several Gardner families living in Sutton at the same time as Charles Gardner, although not directly related. But, it is possible that this is his son, Charles Leslie Calhan Gardner, photographed by Knights-Whittome in April 1907.

Although Charles Gardner’s sister-in-law had worked as traffic staff for LBSC before her marriage, there was only one woman working at Sutton Station before the war. Mary Ann Wakefield was the widow of the Head Porter, and was the Ladies’ Waiting Room and Comfort Room attendant, earning 12 shillings a week in 1907. This would change when war was declared in August 1914.

During the war, the railways were taken over by the Government and most transport roles were a reserved occupation. Train drivers were essential for the transportation of goods, troops, and ambulance trains. The war came early to Sutton Station: the Sutton Advertiser for 7 August 1914 reported that passengers waiting on the station platform saw that the 7:20PM train to Horsham was filled with commuters as usual, but that several compartments were guarded by soldiers with bayonets. This is because about 80 German suspects were being sent from London to Horsham, where a detention camp was being set up.

But, station clerks were not in a reserved occupation, and the early days of the war saw many of the young men that Charles Gardner would have known join the rush to enlist. Although retired by now, Charles would have had a sense of pride in these young men stepping up to fight for their country. His own son, Leslie, enlisted and served from 1915 – 1919, returning to work for LBSC after the war. Young clerks, such as John Cox and William Stevens, volunteered in September 1914, and they were replaced by young boys leaving school – until they themselves were old enough to enlist as well.

John, who had joined Sutton station staff in 1912, was from Cuddington. He was killed in action in Flanders with the King’s Royal Rifles in 1915, aged 20. Did Charles remember the young clerk? Albert Handley, from Dorking, was a Sutton telegraph clerk who enlisted in 1915. His telegraph skills would have been an asset to the war effort, and he was sent to the Balkans with the Royal Engineers. He died of wounds on a hospital ship in 1918. Ernest Parker, a signalman from Banstead, had only started work at Sutton station in June 1914 when he volunteered in September aged 19. He survived the war and came back to work for LBSC. George Harman was a railway goods carman earning 23 shillings a week. Carmen were employed by railway companies for local deliveries. George had been invalided out of the Navy, yet in September 1914, whilst working at Sutton station, he volunteered and went to work at an Ambulance Base Hospital with the British Expeditionary Force. He, along with other Sutton Station volunteers, survived the war – but several were wounded or returned with shell shock. In 1914, there were over 700,000 railways workers in Britain – over 100,000 enlisted and over 20,000 lost their lives.

It was not until 1915 that women began to work as clerks at Sutton Station. Miss Ivy Jessup started work in October 1915, aged 15, and earning 10 shillings a week. Miss Vera Collins joined in August 1916, aged 15, also earning 10 shillings a week. Miss Lily Woolf began work in October 1917 aged 14 as a clerk earning initially 5 shillings a week whilst training, and then 10 shillings a week once qualified. And Miss Winnifred Tiller also started training in February 1918, aged 14 – her father was the Station Master at Ewell. Would Charles Gardner have approved of women working in his station? Perhaps – his own daughter was a single working woman.

After the war there was a ‘surplus female population’ of over one million. All the female clerks at Sutton resigned at the end of the war to make way for the returning men. Most of them later married, but working single women were often perceived as taking away work from men who needed to provide for their families.

Charles Gardner’s daughter, Edith Bessie, did not marry. After his retirement, Charles (now widowed) and Bessie moved to Lenham Road where they lived together until his death in 1938. Could this be Edith Bessie Gardner photographed in 1904?

Bessie, born in 1885, trained as a Secretary and Shorthand Typist. Office clerks had traditionally been male and, until the invention of the typewriter in the mid-nineteenth century, all documents and correspondence were handwritten. The typewriter contributed to changes in the working life of women. There were many opportunities to train as professional typists and this was accepted as a suitable job for a woman – although she would be paid less than a man and would be expected to leave upon marriage. It also provided work for middle class women who had not previously worked – and gave those women the opportunity for financial security in a safe environment. Pitman’s Shorthand System had been devised in 1837, and by 1888 there were Shorthand exams. Typing exams were introduced in 1891 by the Society of Arts. But where did Bessie learn her skills?

Epsom and Ewell Technical Institute and School of Art, established in 1896, offered shorthand at evening classes. Perhaps Bessie took the train to Epsom and trained there? Or did she go down the High Street to No. 18? According to the 1908 edition of Piles’ Directory Knights-Whittome was sharing the premises with the T & G Graves School of Shorthand and Typing. It was only there for a year but Bessie, then aged 23, could have decided that she wanted a skill to enable her to be a financially independent woman. She could have worked for the Civil Service, local government, banking or a private company. Whether she was single by choice, or not, those skills meant that she could provide for herself.

Even in retirement Charles Gardner still played an important role in Sutton life. When he left Purley station he was presented with a gold watch, chain and 20 guineas by the inhabitants of Purley – an indication of the respect they held for him. His retirement notice in the Sutton Advertiser also commented on the high regard that passengers had for him. At the outbreak of war several meetings and committees were organised to provide relief for the families of those who had signed up, and Charles’ name appears on several lists of supporters.

In 1915, Charles joined the Sutton Sub-Committee of the Surrey Pensions Committee. The Poor Laws of 1834 assumed that employment would be a person’s main source of income until death; any other support or relief would be from the workhouse. Sutton was part of Epsom Poor Law Union, with a workhouse in Belmont. The conditions there were so unsatisfactory that in 1910 there was a riot about the poor quality of the food! Although nationally people were now living longer, many could not afford to save for ‘retirement’. For instance, Mary Ann Wakefield, born in 1845, continued working at Sutton Station until her late sixties, only retiring in 1914 when she could no longer physically work.

Older people who still needed to work were considered to be taking jobs away from younger workers. The Old Age Pensions Act of 1908 aimed to relieve some of the pressure on the workhouses, and, as these were funded locally, to reduce the cost to local communities. The Act gave a means-tested pension of 5 shillings a week to a person over 70 (7 shillings and sixpence for a couple), and it was funded out of central taxation. The full amount was paid to those with an annual income of less than £21. A claimant needed to have been resident in the UK for 20 years and of good character – there were behaviour tests! The payment was not automatic – claim forms had to be returned to the Postmaster. Charles would have been familiar with Henry Malley who had been the Postmaster at the old Post Office just down the road at No. 14 High Street, and then at the new Post Office in Grove Road. The claim would be assessed by Pension Officers and then sent to the Pensions Committee for approval. Perhaps Charles would have known some of these who applied –maybe some of his old railway workers? The alternative in earlier years for many would have been the workhouse. It must have given Charles a sense of satisfaction to be able to help the elderly in his community. He served on this committee until the 1930s. He was also a councillor with Sutton Urban District Council from 1915 until 1927.

In a life that spanned over 80 years Charles observed many technological changes – the supply of gas and electricity to houses, a water and sewage system, telephones, trams, cars, aeroplanes. Now the horse drawn carriages outside the station have gone, the original station buildings were demolished and rebuilt in 1933, the line was electrified by 1938, and there are no longer telegraph clerks or ticket collectors. Women now work at the station, there are electronic noticeboards, gates and ticket machines, and the traffic on the High Street is a fast mix of cars, motorcycles, and buses. The shop use and fronts have changed, yet the buildings above appear little changed from when Charles stood outside his station at the beginning of the 20th century. Charles would still feel at home!

Resources Used:

- UK, Railway Employment Records 1833 – 1956

- UK, Railway Employment Records (1914-1920 Staff on active service)

- Sutton Advertiser 7 August 1914

- Sutton Advertiser 12 January 1914

- Piles Directory for Sutton – various years

- https://www.yourlocalguardian.co.uk/news/4825219.remembering-the-1910-belmont-workhouse-porridge-riot/

- https://www.networkrail.co.uk/stories/wwi-and-the-railway/#:~:text=About%2013%2C000%20women%20worked%20on,in%20to%20fill%20essential%20functions.